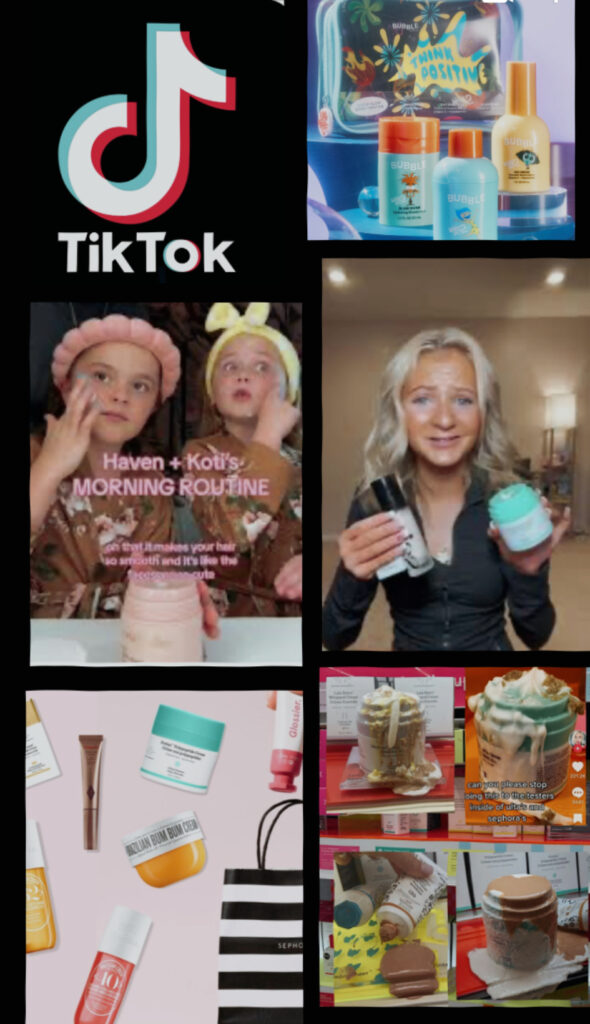

If you know a tween girl, you most certainly have heard the term “preppy.” Defined by colorful, feminine, and expensive clothes/accessories (e.g., Lululemon, Stanley cups, Kendra Scott necklaces), preppy is one of the biggest beauty trends among pre-adolescent girls. The term “Sephora girls” has also become quite popular, referring to tween-aged girls interested in the cosmetic store, Sephora. “Sephora girls” are known to buy hundreds of dollars’ worth of expensive skincare and make-up products in order to achieve beauty goals (Camero, 2024).

Dear Hannah Prep is a TikTok account for a tween boutique in Texas that has 15.7 million likes as of June, 2024. Dear Hannah Prep showcases a lot of the beauty norms through “get ready with me” videos, where girls advertise what products they use in their morning skincare routines.

In addition to teaching beauty tips, these trends teach consumerism at a young age (8-11 years old). As an example, this summer, Disney partnered with the skincare brand, Bubble, to promote their animated film, Inside Out 2 (Segran, 2024). Indeed, the beauty industry has reached a global net worth of $532 billion, demonstrating that targeting pre-adolescent girls is a strategy that works (Danziger, 2022).

Engaging in beauty work is not new, but some have raised concerns that young girls are buying products they do not need (e.g., retinol) and/or that may damage their skin (e.g., skin rashes, allergic reactions). Additionally, these skin care products are quite expensive, creating competition and hierarchy among those who can afford these products and those who can’t. Years ago, psychologist Renee Engel, introduced the term beauty sick to explain that although girls may be aware of the unrealistic beauty images, they live in a beauty-sick culture that is near impossible to ignore.

In 2023, the United States Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued an advisory about the harmful effects of social media, especially among adolescent girls, highlighting that it may perpetuate body dissatisfaction, disordered eating behaviors, social comparison, and low self-esteem. Compared to their peers, for example, young girls who reduced their social media use by 50% for just a few weeks experienced improvement in their body self-esteem (Thai et al., 2024). Social media, and especially TikTok, is, unfortunately, a major transmitter of a beauty-sick culture.

Of course, not all tweens internalize harmful aspects of a beauty-sick culture, and there are actions that adolescent girls can take to prevent harm. The tripartite model of social influence cites parents, peers, and the media as influences on body, so there is opportunity to counter problematic messages at every level of influence. Parents and caregivers can encourage tech-free zones, teach kids how to be critical consumers of social media messages, and review healthy (and often simple) skincare/beauty routines. Peers can work to support each other in healthy practices by actively critiquing unrealistic beauty norms and balancing social media use with other fun activities. Finally, social media influencers can create content that supports critical consumption of beauty norms and activities. Social media use is nearly universal among young people, with almost 95% of people ages 13-17 reporting that they use it (Thai et al., 2024). There are certainly positive aspects of social media – it can be a powerful tool for information, creative expression, and connection. However, messaging related to excessive (and expensive) beauty work cannot be ignored, and we all owe it to the tweens in our lives to get real about its harms.